VERTICAL LIMIT: Endless Journey

Solo Exhibition:-

Husin Hourmain

1st August – 5th September 2023

Core Design Gallery, Subang Jaya

*Click on images to zoom in

VERTICAL LIMIT: An Endless Journey

As humanism spread as an important intellectual movement, it acquired greater sophistication in dealing with language and history.

Philip M. Soergel (ed.), ARTS & HUMANITIES:

through the Eras Renaissance Europe 1300–1600

(2005)

In his sixth solo exhibition, Husin implicitly offers the idea of Humanism with an individual approach. It is Humanism presented through a personal aesthetic style. Humanism was born and overpowered mythological and theological epics that predominated in Europe before the Renaissance era. An ideology with the belief that humans are the measuring point in all considerations, Humanism affects our lives to this day. Humanism emerges almost impeccably and even becomes the spirit of virtually all areas of human activities and daily life. Especially when it comes to creative activities, the orientation always returns to the human dimension.

Humanity in Husin’s mind and creativity stands out in several facets. They range from the ideational aspect to the abstract symbolic-expressive visual style that Husin uses. It is clear that the particular style makes it easy for Husin to explore various meanings and interpretations of the idea of humanity.

As Soergel states at the beginning of this article, Humanism’s attempt to stick to its purely original style and language – Latin – produced paradoxical effects. Latin was no longer the living and thriving language it had been for most of the previous time. New languages and vocabularies were constantly being introduced from time to time. A number of scholars and writers realized that Latin was no longer developing as a vital language in Europe. They thought that the future of humanity lay in regional languages: English, Italian, French and Dutch.

The emergence of such “languages” opens up opportunities for everyone to express themselves individually. Through visual language, Husin wants to reinforce an attitude and belief that art is not only concerned with the exploration of art itself. He continues to believe in and celebrate the philosophical concept of traditional Eastern art which prescribes that art should be a part of everyday life – religious, social and environmental life.

Dr Mikke Susanto

Curator

Objects of Painting and Aesthetic Concept

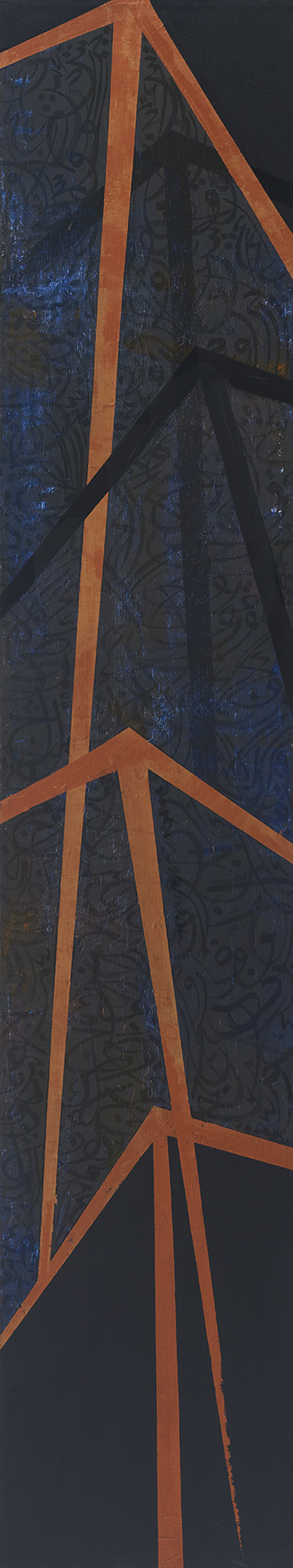

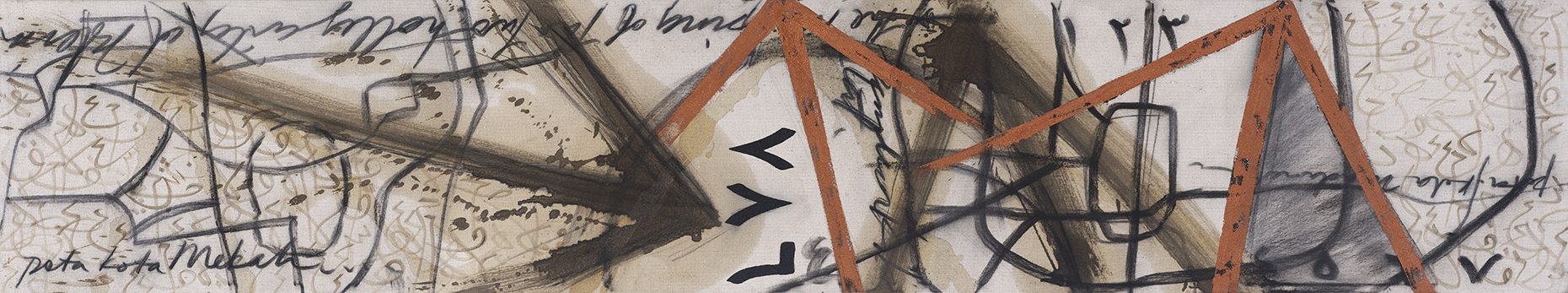

If you take a closer look, you will find a number of special objects in Husin’s paintings in the exhibition. These objects are Jawi script or Latin script, the architecture of the holy city of Mecca or the hills of Arafah, or the details of the structure of the Kaaba and strokes of several abstract structures. They articulate a number of aesthetic views and artistic aspects that are different from those expressed by the works in Husin’s previous exhibitions.

His first solo exhibition “Energy” (2004) and the second one “Zero to Something, Zero to Nothing” (2008) have been a vehicle for Husin to represent his existence as a professional artist, a departure from his previous status as an amateur painter. It should be noted that Husin declared himself as a professional in 2003. During the period, he worked on canvas and pigments to explore colors and forms in the process of exploring his identity as an artist. At that time, he had applied the drip painting technique. It was only in his Allah-Study (2006) and later that the narrative about the idea of monotheism entered his paintings. Husin decided to explore narrative aspects in his works in 2006.

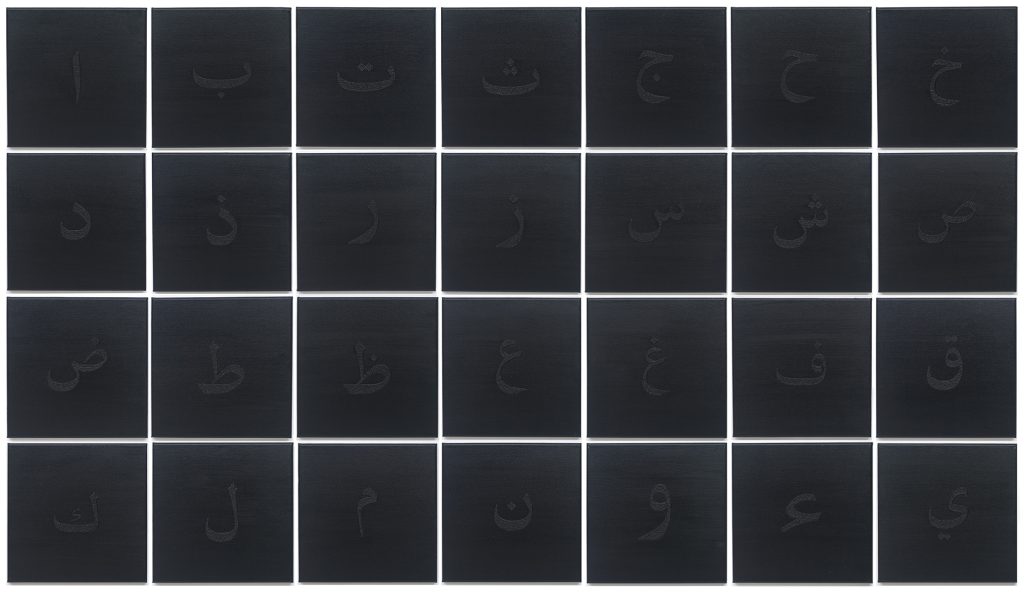

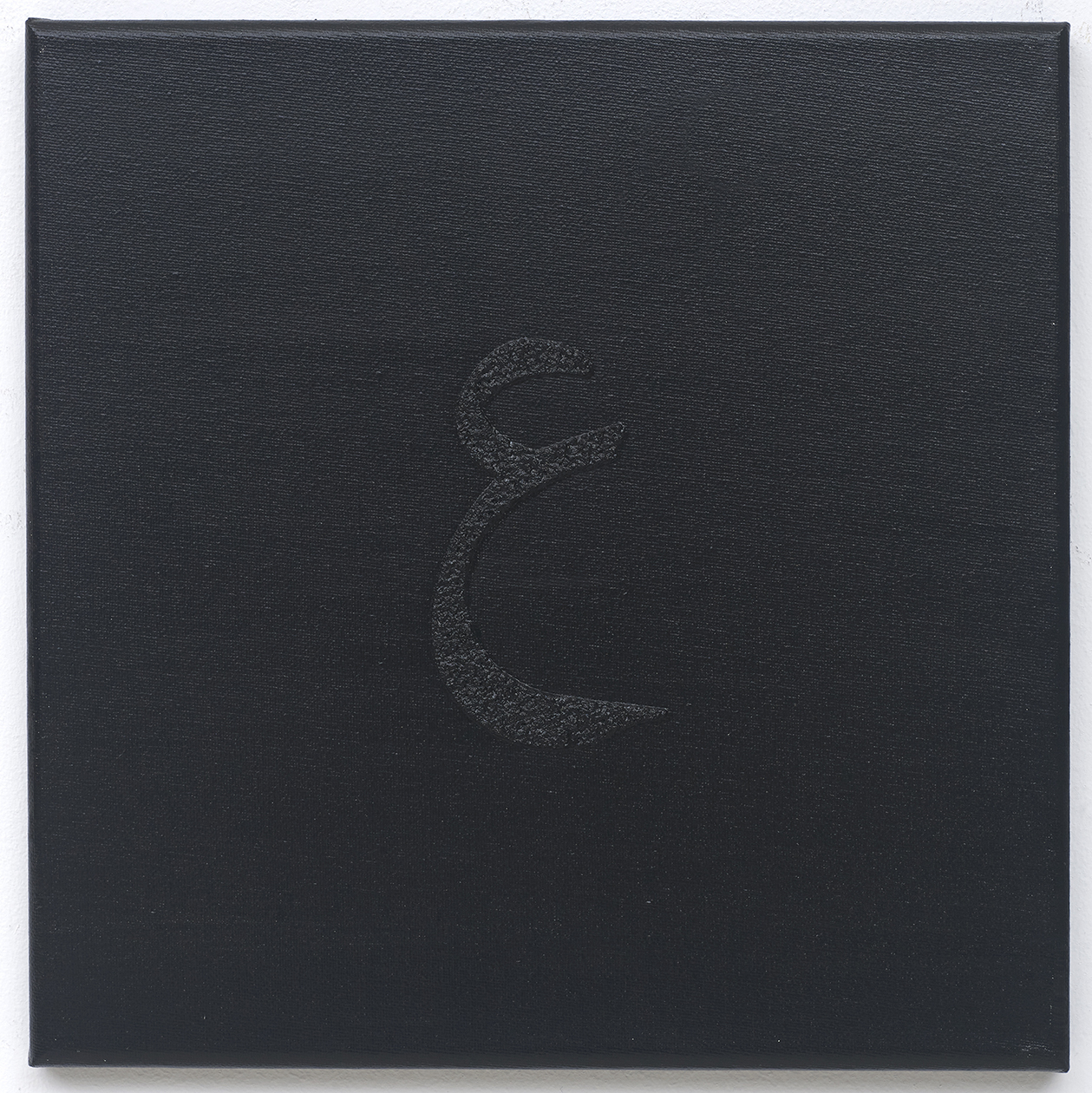

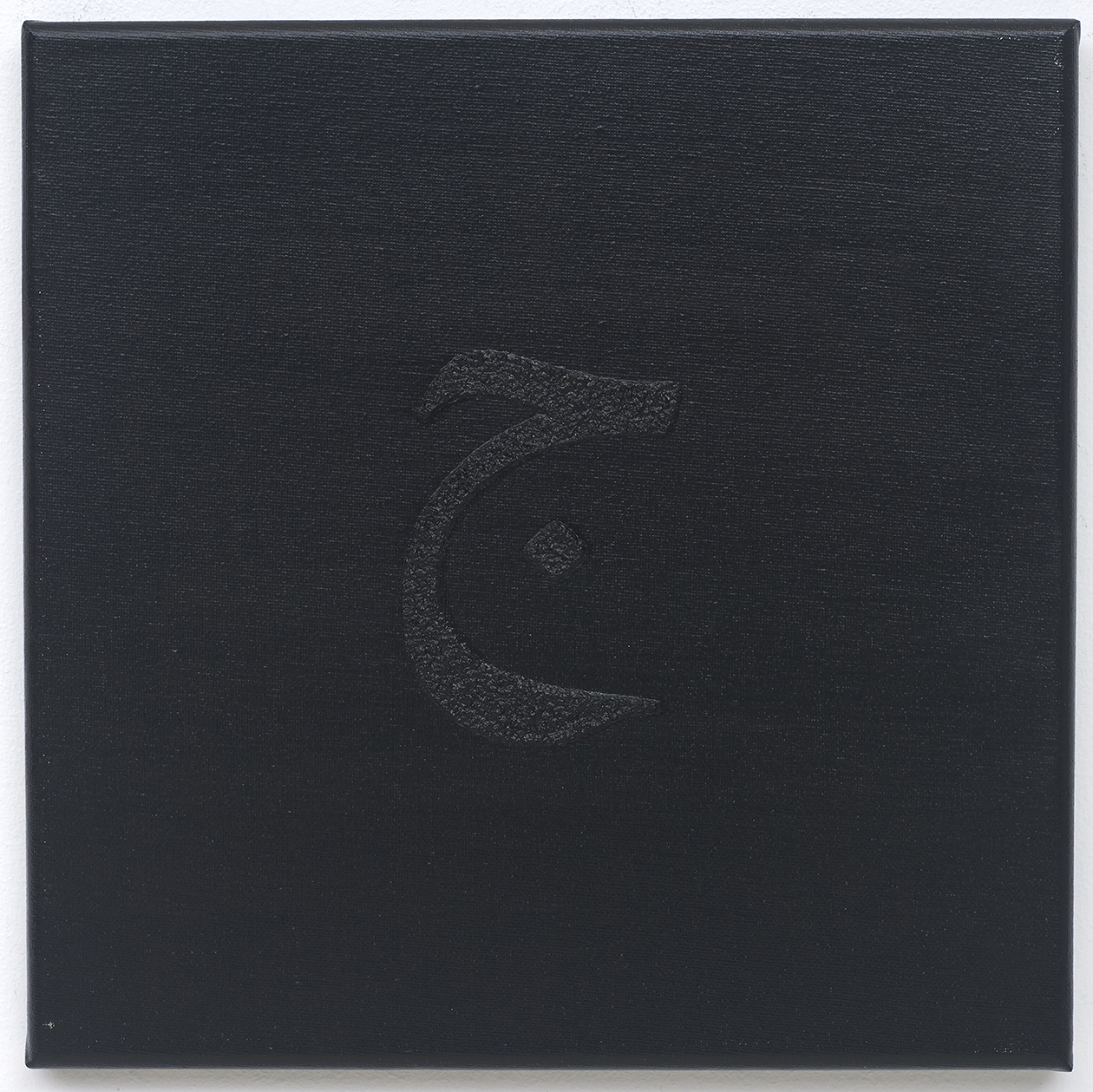

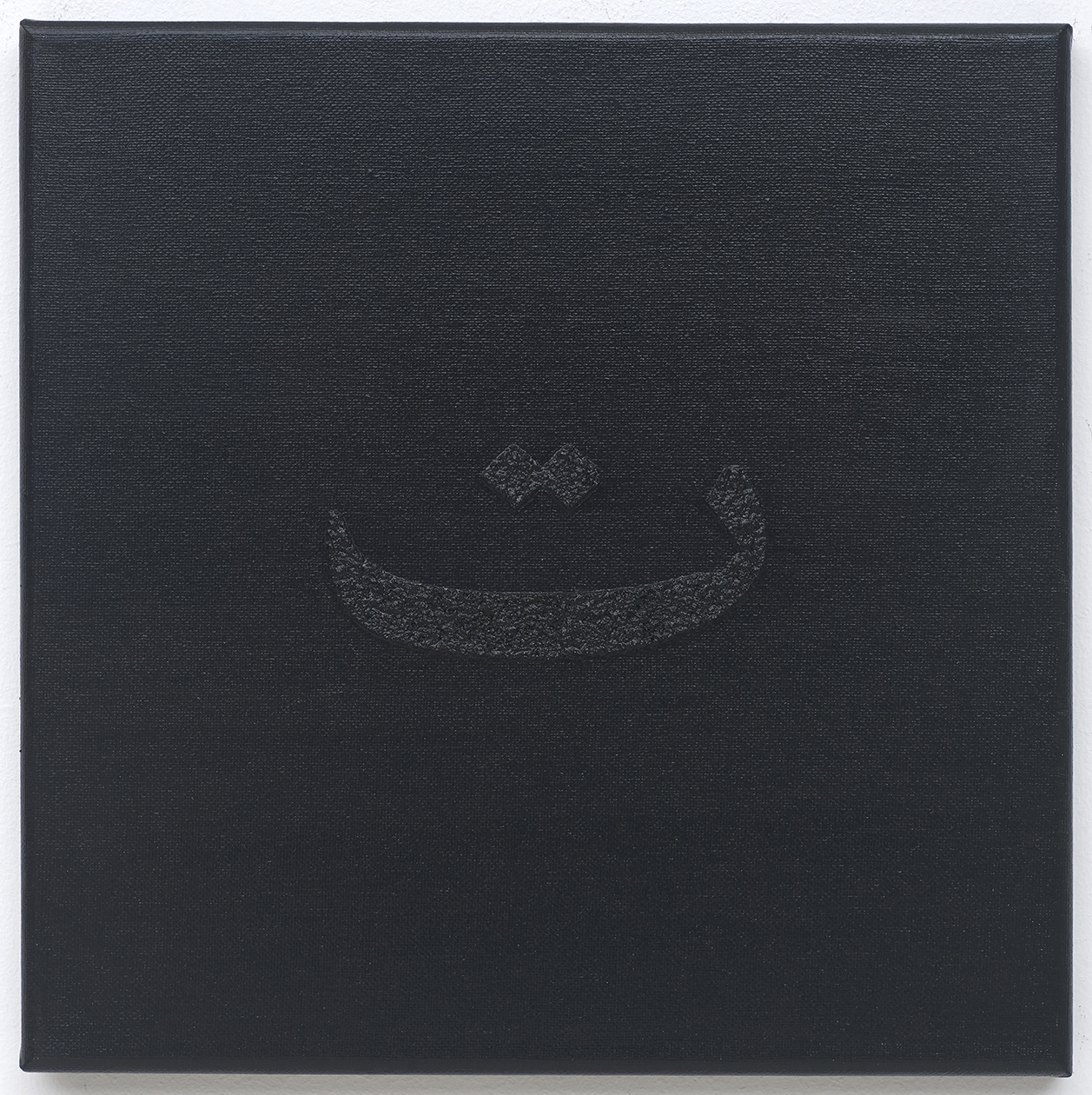

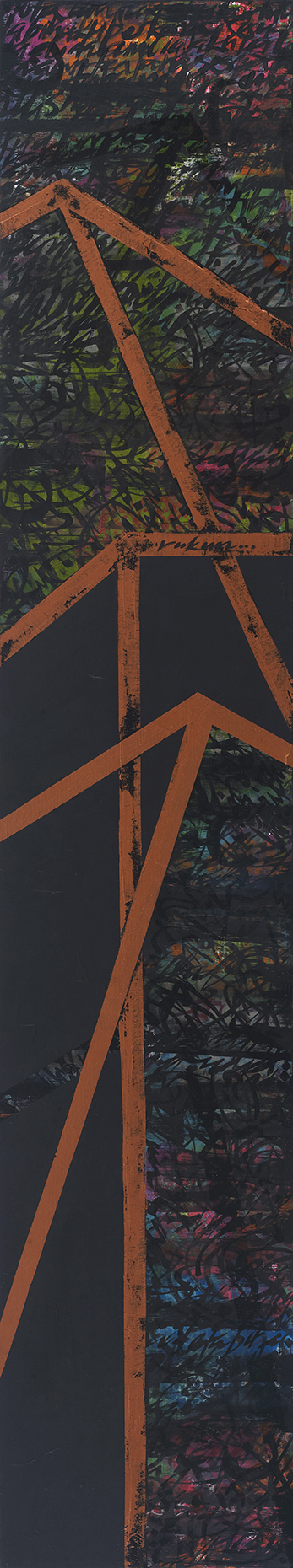

In his third solo exhibition “Awal Huruof, Asal Huruof” (2013), Husin’s paintings feature calligraphy in a semi-expressive decorative style. In each work, he explores a single letter that is formed from smaller letters. Arabic letters Alif to Ayn are composed with spontaneous color strokes and paint drips. On one side, such a single letter is filled with rhythmic and repetitive strokes of the same and much smaller letters. The strokes are spontaneous, yet still form a defined letter pattern. Husin’s hands move spontaneously as if he is making a sketch, creating fantastic color nuances. This period is Husin’s early stage in exploring Jawi script.

Husin presented something different in his fourth solo exhibition “Aku: dalam Mencari Rukun (2018). The idea is rooted in the Islamic Pillars of Faith. An important note from this exhibition is that Husin composed non-painting works (such as Kun Fayakun, 2018 and Korban Ibrahim, 2016-17) as part of his show. Another note is the emergence of non-letter objects (calligraphy), such as rectangular shape, block as a representation of pillar, exploration of amorphous and organic forms and abstract expressionistic styled compositions. In the exhibition, Husin succeeded in penetrating the realm of ideas that are freer than just letters (calligraphy) and drips of paint.

Husin’s fifth solo exhibition “Salam @Peace” (2021) was held when the Covid-19 pandemic was starting to subside. In the exhibition Husin began to participate in the trend of social reflection, while still using letters (calligraphy) as a visual basis. Twelve mixed-media paintings in the exhibition visualize single letters painted in various colors. The results appear as the paintings of “a flower garden on the edge of a threatening cliff”. It is clear that when he was in the process of making the paintings, Husin saw that the world had gone through a dark period that had took its toll on millions of people. He wanted to call on everyone to live in high spirits again.

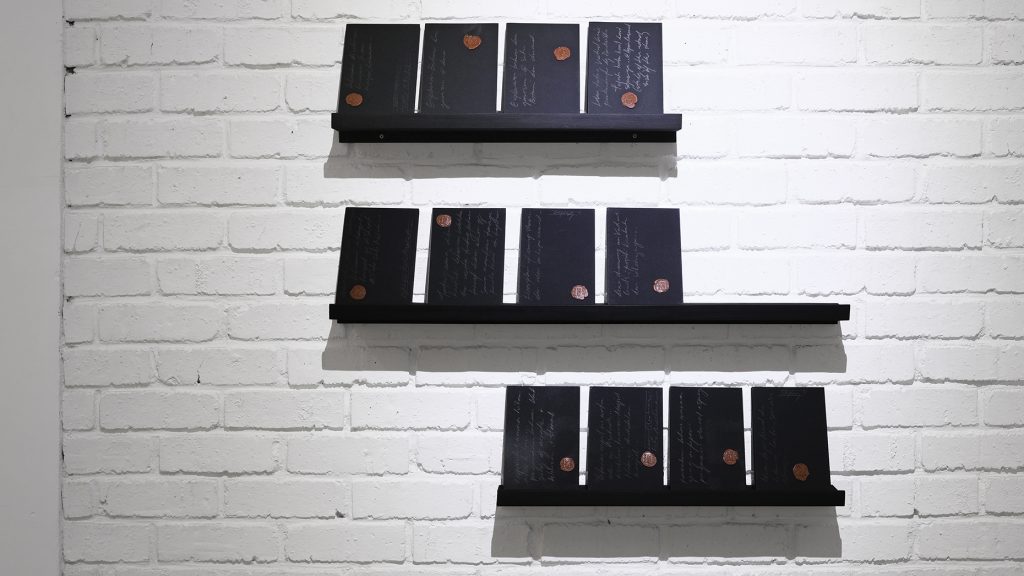

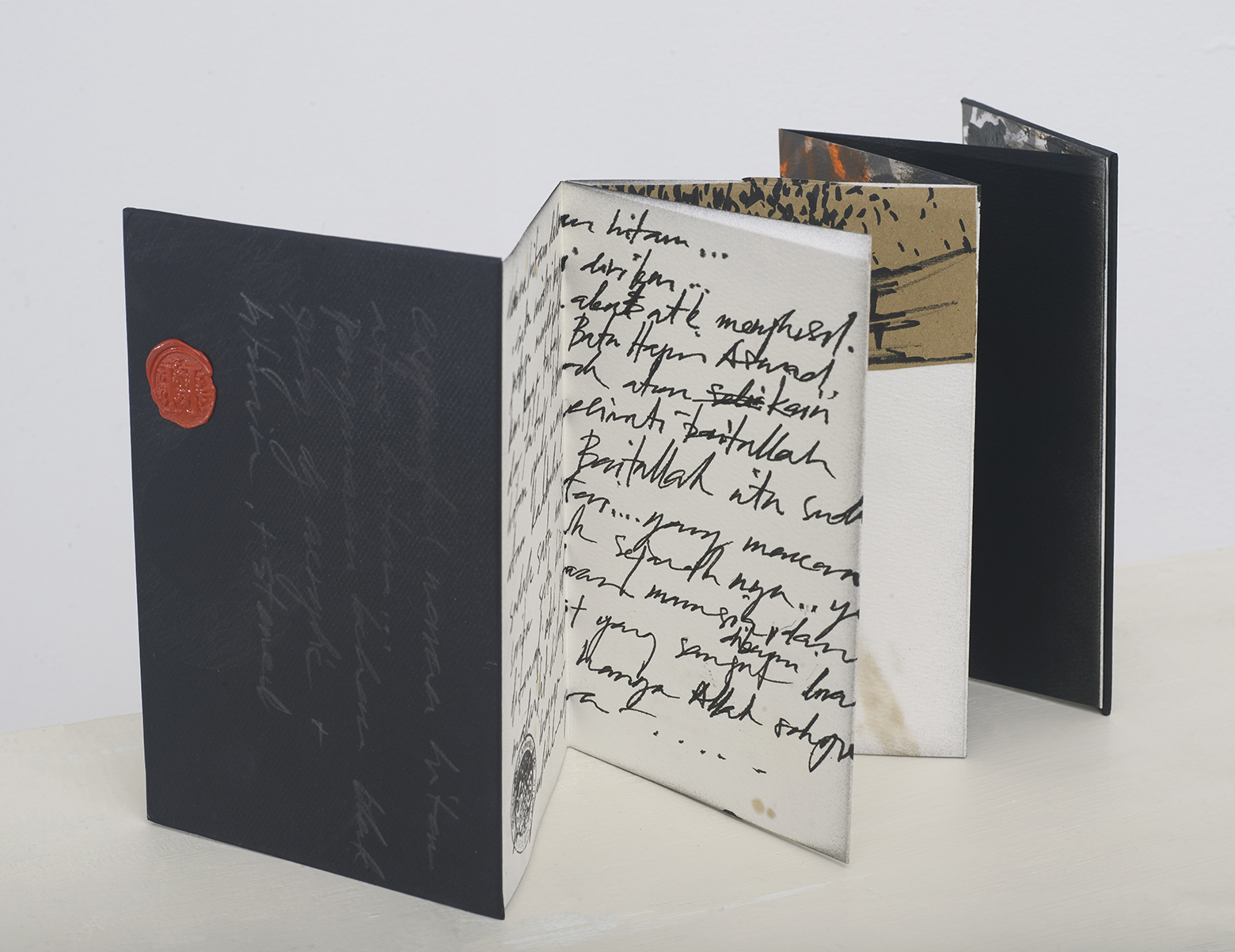

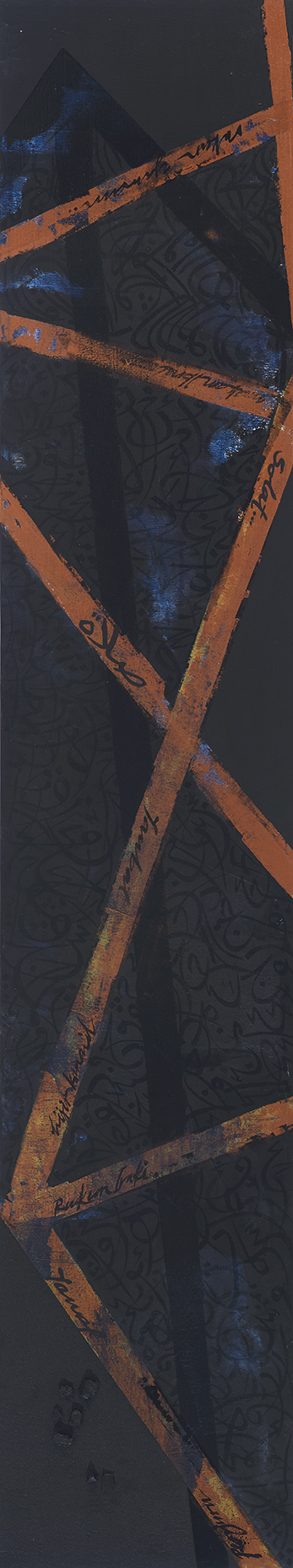

The current solo exhibition is evidently different. Husin still uses Jawi script (and Latin script) as a medium of expression as in his previous exhibitions. However, now the letters are combined with social and personal narratives. The ideas come from the Pillars of Islam and the Pillars of Hajj, accumulated through Husin’s experiences as a Malay Muslim. Husin’s Umrah pilgrimage in February 2023 is a significant starting point of the exhibition. The main markers are the use of Jawi script, the emergence of post-calligraphy discourse, the black color in the paintings, and 12 specially presented diaries.

Let’s examine them one by one.

Jawi Script x Latin Script

It is important to observe the use of Jawi script and Latin script in Husin’s paintings. The use of those scripts is part of Husin’s respect for humanity. For Husin, Jawi script opens up the possibility of new articulations and meanings about cultures that have been around for a long time in the archipelago. On the other hand, Latin script in Husin’s paintings appear as support that carry a different concept.

The Jawi alphabetic tradition has the story associated with the spread of Islam. Jawi script was developed by Syekh Jawini, a language teacher who lived at the end of the 13th century in Samudera Pasai, Aceh. Jawini pioneered the use of Jawi script in Malay writings. Its use extends to Malay (Malaysia, Brunei, Siak, Pahang, Terengganu, Johor, Deli, Kelantan, Riau, Pontianak, Palembang, Jambi, Sarawak, Musi and other dialects) and other languages such as Acehnese, Betawi, Banjarese, Kerinci, Minangkabau and Tausug. In Java, the script is called Pegon, with a number of differences from the original Jawi script.

Jawi script is based on Arabic script and is used for writing Malay. Thus, it is inevitable that there are additions or modifications to the letters in order to accommodate sounds that do not exist in Arabic. The earliest evidence of this Malay Arabic script is found in Malaysia, namely the Terengganu Inscription from the 14th century AD. Today, Jawi script is used in almost all areas of Terengganu, Kelantan, Kedah, Perlis, Patani and Johor.

For a long time, Arabic script has played an important role in Malay society in the archipelago. Its use is very extensive. It is used as a medium in almost all matters, including administration, customs, and commerce. In fact, Jawi script was used in important treaties between Malay kings and the Portuguese, the Dutch or the British. Even more interesting, part of the Malaysia’s declaration of independence in 1957 is also written in Arabic script.

In view of such facts, the use of Jawi script in Husin’s works is not without reason. The reason could be that he is a Malay Muslim. It could also be that the place where he lives has a very old cultural heritage. What is clear is that Husin thinks that he has grown in, and has become a part of, the history of the development of Jawi script to this day.

The first use of Latin-Roman script in the archipelago was officially introduced in 1536. The script was used in the first school in Indonesia, founded in Ambon by the Portuguese ruler, Antonio Galvao. In the following century, Latin script was used for writing Malay in the Christian scripture. Furthermore, it had become the “unifying” script for local scripts.

Thus, the history and the existence of the two scripts in the context of the times seem to be very different. Jawi script belonged to the pre-colonial era. Latin script spread in the atmosphere of colonialism in almost all parts of Southeast Asia. The spread and the history of Jawi script and of Latin script in this context, in particular, are manifested simultaneously by Husin in his works. Husin wants to argue that the history of, and the differences between, the two languages/scripts do not necessarily cancel each other out. We must preserve both scripts as an effort to integrate us in the essential: mutual respect for fellow human beings

Post-Calligraphy

Husin’s personal life is a source of an interesting story. Husin lives in a village in Kuala Kangsar, Perak state. His studio is spacious and has good facilities. It has a library with an excellent collection of art books, a comfortable computer desk, two guest rooms with clean toilets, and a prayer room with a very beautiful spatial design for a private facility.

The studio is far from the hustle and bustle of a city. The cool air makes you feel at home. Husin grows durian, mango, coconut and other trees as a hobby. In his residence, decorated with hills and shady trees, Husin manages to record the glory of nature and God through his paintings. Living far from big city and art center, as well as the absence of busy life, allows Husin to map himself in various matters and interests in his life and art.

Husin told me that living about 3.5 hours away from Kuala Lumpur makes it easier for him to abstract various topics and realities into artworks. During my curatorial work, when I stayed at his place for a few days, I saw Husin as a devout Muslim artist. Whenever it was time for prayer, from dawn to evening, he would drive to the mosque in a neighboring district to pray. His studio, adjacent to the Iskandariyah Palace and the Yellow Palace, has become a means of exercise and a source of inspiration for him. The point is that from waking up until going to bed he lives a relaxed life and is humble to anyone, without losing the habit of taking notes (sketching) on paper available in his studio.

Husin’s closeness as a Muslim to the nature around him and his private routine with the Archipelagic Malay tradition is manifested in an artistic style that I call post-calligraphy.

The designation reflects the development of calligraphy. Calligraphy occupies a place of honor in the development of Islamic art. This art of arranging dots and lines in various shapes and rhythms has never ceased to stimulate human memory of the state of mind and divinity. Calligraphy is actually a designation that leads to the embodiment of one’s feelings through letters.

According to Hossein Nasr, there are several important points in calligraphy. Firstly, the genealogical relationships of calligraphy to Ali (representative of Islam after the Prophet), some of the first Islamic spiritual leaders of Sunni Sufism and the Shafi’i imams. Secondly, calligraphy is made by human hands and continues to be consciously practiced as a human emulation of the Acts of God, even though it is “far from perfect”. Thirdly, traditional calligraphy is based on a science of precise geometric rhythms and intricacies.

Such a notion of calligraphy is insufficient in recent developments, at least for Husin. The art of calligraphy today is not just an artistic handwriting of Islamic scriptural dogmas. There is a number of reasons for proposing the concept of post-calligraphy.

Firstly, Husin’s works contain a discursive awareness that is more directed towards locality. Locality is related to issues, stories, customs, wealth of resources, and the cultures surrounding the artist’s life. Husin makes such relations in interesting ways, for example in Tawaf (2023) or Study of 678 (2023). In Study of 678, he takes the essence of the Pillars of Hajj and the symbolization of the number 678 as the personification of the prayer for all activities: Bismillah (in the name of Allah). In Tawaf, he implicitly takes material from rubber plantations around his village as part of his social criticism.

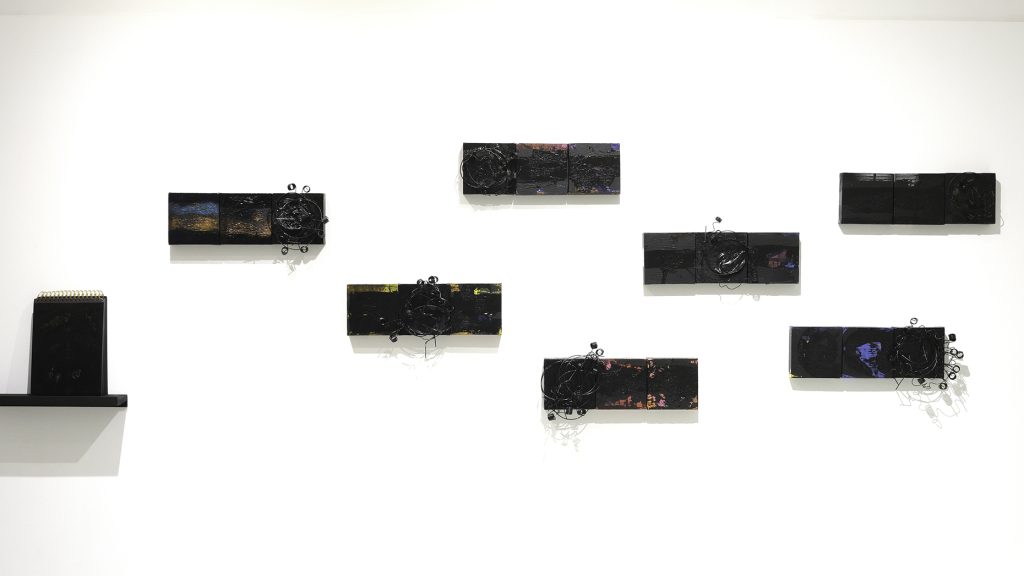

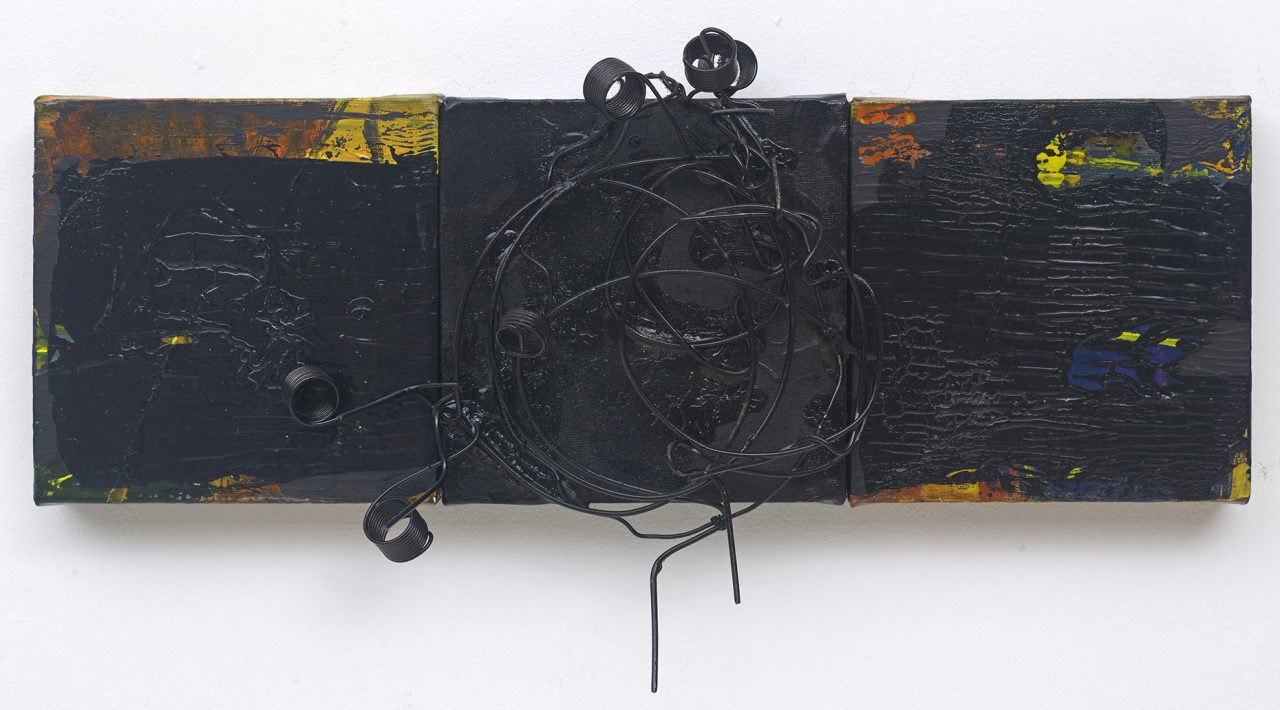

Secondly, Husin has a broad awareness of medium in his art making. Apart from paintings, Husin has also presented works made of ceramics, wood, glass bottles, iron wire, books, etc. The complexity of the medium is not only experimental and an expression of individual experience, but also offers a narrative that is connected to many issues. On the other hand, the issues of medium aim to surprise and “entertain” the viewers. It is important to note the level of technical complexity and the type of material dematerialized with respect to the context and the concept of the exhibition.

Thirdly, the presence of the artist’s social awareness in viewing the world and human life. So far, calligraphic works have focused more on aspects of the vertical relationship between humans and Allah. Or, most of them are calligraphic writings about human philosophical awareness on religious issues or dogmas with conventional visualization. Husin’s Study of Endless Journey (2023) carries his personal notes from his imagination and experiences. He makes such notes everywhere. This point is often absent in traditional calligraphers because they typically forget the contextual social dimension.

Fourthly, there is a personal exploration and “play” of Jawi script in Husin’s works. In this case, Husin does not inscribe Jawi script in a conventional style as in the tradition of “beautiful handwriting” in general. The beauty of Husin’s Jawi writings lies in their spontaneity, expressiveness and unplanned. His hands move dynamically and naturally, writing elegantly. All parallel to the style of abstract expressionism that underlies his creative work. Husin’s loosely styled Jawi letters give the impression of being unreadable; they even feel like phoney Jawi letters. Such an impression is one result of the exploration of letters that knows no bounds. It is natural that Husin’s Jawi letters, for example in Kiswah (2023) and Perspective & Perception (2023), sometimes seem to have no meaning, even though this is not the case.

Based on these four points, Husin’s works can be read as a manifestation of the development of post-calligraphy. Husin’s success in raising the essence of calligraphy reveals an awareness that calligraphy is not only about divinity, but also contains expressions of the human soul and experience. Calligraphy is not merely a passive “skill” (an expression of resignation), but it can also be a “war” equipment for a better life. The point is that Husin wants to make letters appear as an image of the plurality of humans as God’s creation.

Black Paintings

Sincerity is like a black ant on a black stone on a pitch-black night. It exists, but it is very hard to see (anonymous)

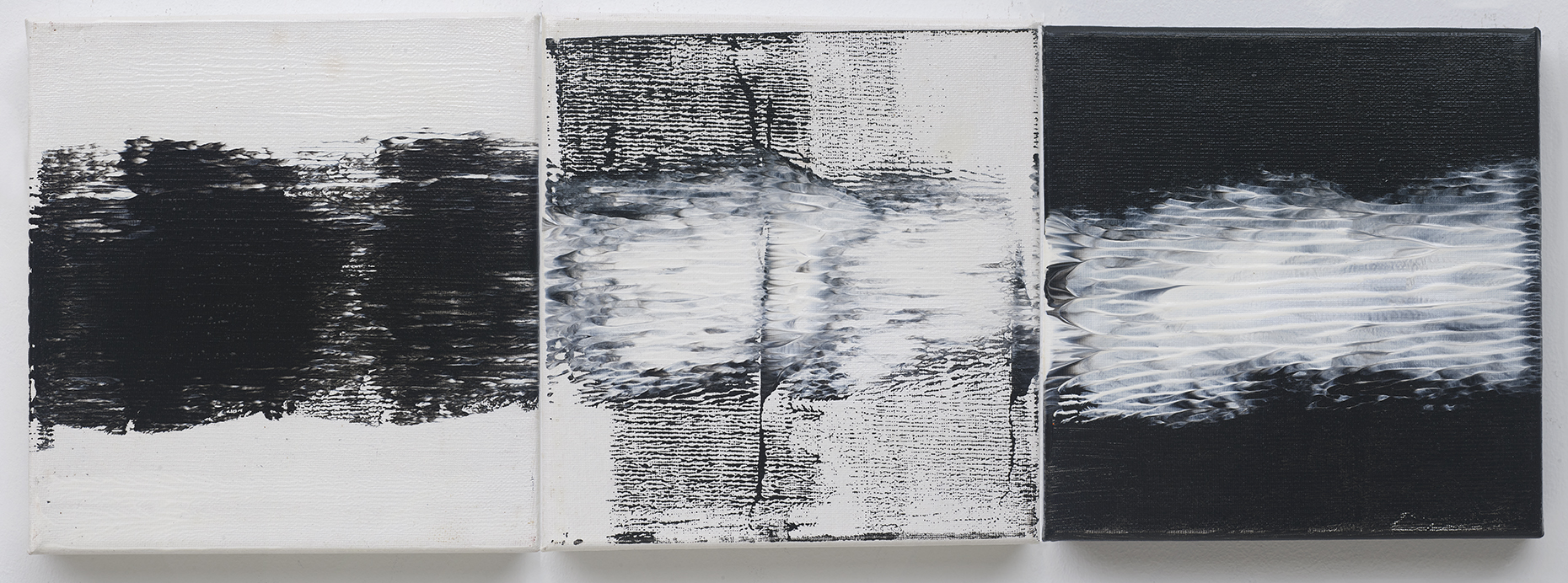

In addition to Jawi and Latin scripts, black color predominates in Husin’s works. Black is very symbolic for many people. It has many layers of meaning. Sometimes black (and white) is not considered a color. Black and darkness are often seen as natural phenomena in every space and time in the universe. They are always there in all life stories. In color theory, black is a mixture of all colored pigments. White is a mixture of colors in light waves. Hence, black (and white) is both ordinary and extraordinary for those who are able to interpret it.

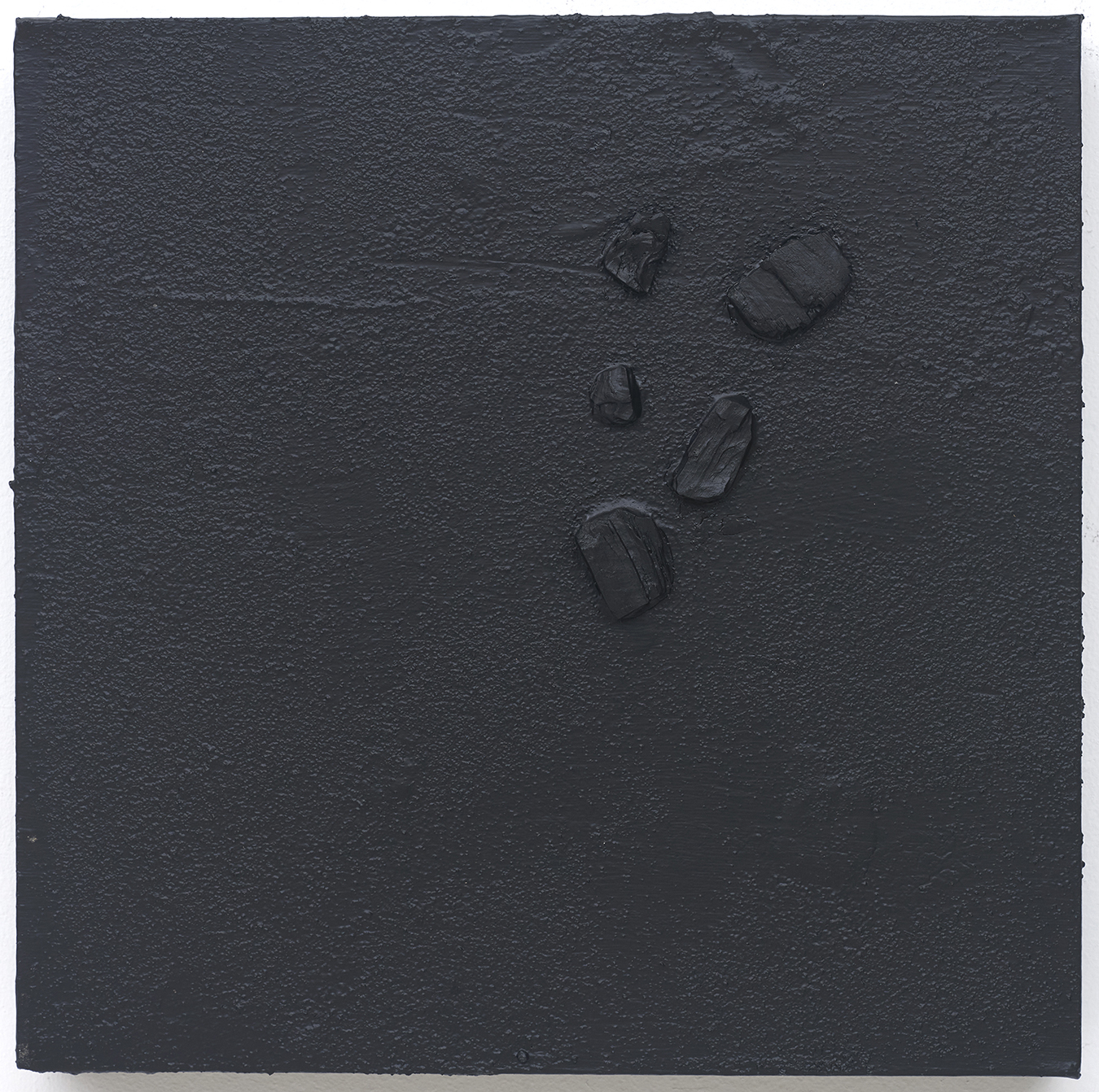

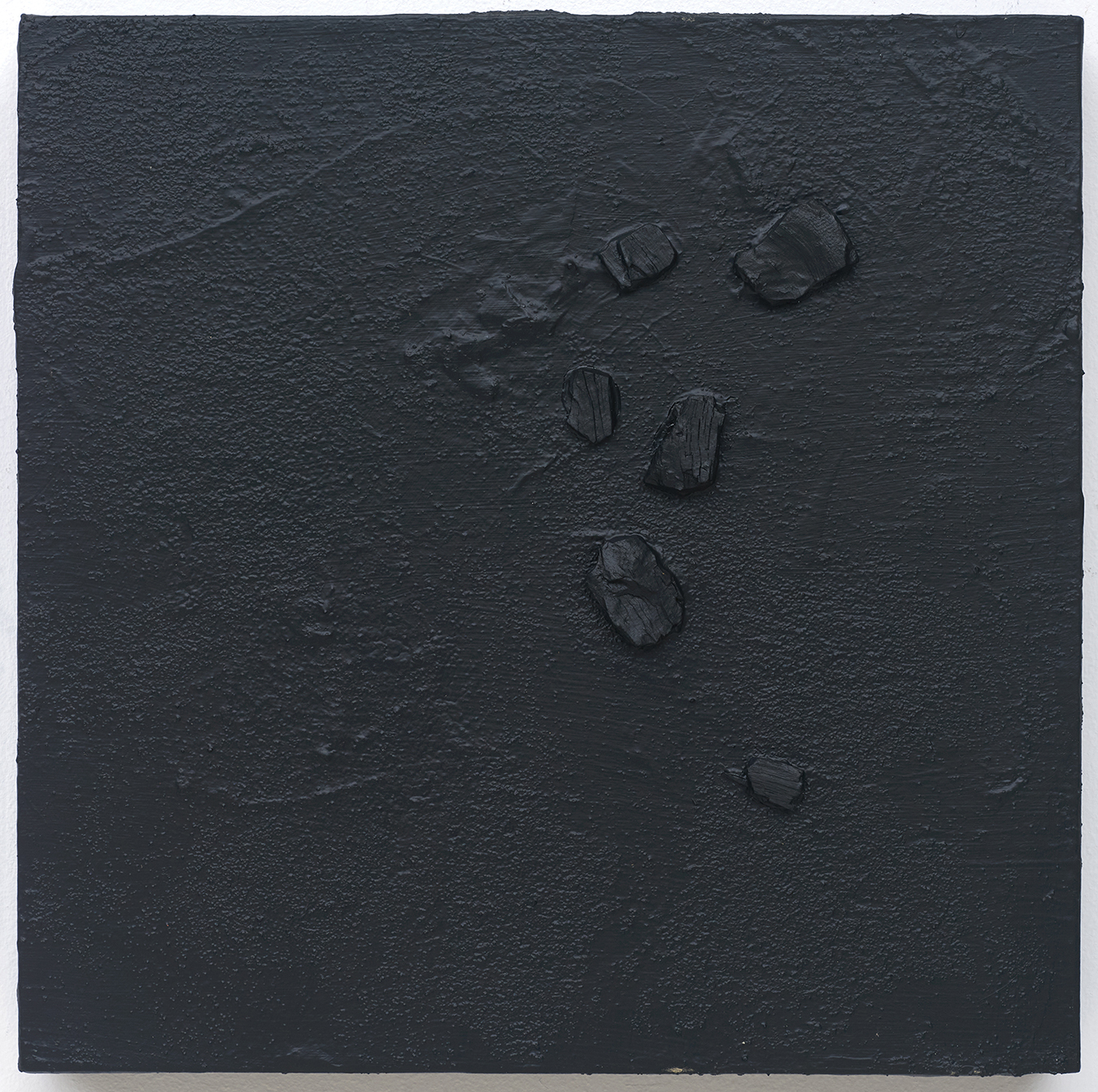

In Husin’s paintings, black can be read as having three significant meanings. Firstly, Husin wants to show an exploration of black color in the framework of visual psychology. By linking the (depicted) object with the medium (canvas), both of which are black, he wants to show that there are different dimensions. In short, he challenges us, connoisseurs of his works, to be more sensitive to space and time, dark and light, as well as abstract (non-physical) things. His painting 28 Alphabeth of Jawi is the perfect example.

Secondly, in a certain perspective, Husin has performed symbolic work by reading the story of the black stone (Hajar Aswad) as part of a religious narrative as well as a social narrative. His paintings Tujuh Batu Hitam (2023) and Kiswah (2023) are interesting examples. Black has a role as the object of the paintings. The materials, namely charcoal and blackened canvas, eventually become a significant narrative. This means that Husin intends to embed the “spiritual” aura of ordinary material onto the canvas. Husin’s black paintings have the meaning of celebrating darkness as a way to understand a life that is still mysterious, non-physical and intangible. They are about the past, the future, death, birth and fortune, or about the Judgment Day and the Hereafter.

Husin also explores the potential of black as a “virtual” or symbolic space and a medium for contemplating social issues and his surrounding communities. The global Covid-19 pandemic is one of the reasons for the darkness of the present and the future. Uniquely, Husin also depicts squares or cubes in various positions in opposite colors (white or other colors). Even though they are painted in white, these basic quadrate shapes are in essence the black-clad structure which is the center of Muslim spirituality: the Kaaba.

Thus, it is clear that through the quote about “sincerity” above, Husin argues that darkness is not non-existence, but something sublime. It exists, although it is hard to see.

Vertical Limit

Based on the various assumptions above, it is obvious that Husin is a man who has experienced clashes of civilizations. He lives in a post-modern spirit. He knows and understands the local wisdom inherited from his ancestors. He adheres to the social ethics that shaped him as a Malay citizen.

However, he is also a global citizen who faces the complexities of civilizational changes. Husin cannot remain silent in the face of various natural, socio-political and environmental phenomena and upheavals around him as well as those that are geographically far away.

Through his works, we can learn that human life is never stable. The journey of human life is never ending and never light. Human life has virtually limitless problems, both in human relations with others and vertically with God. That is the meaning and essence of humanity in Husin’s paintings.